Plathanthera blephariglottis [pollination & insect interaction]

Northern White fringed Orchid [Platanthera blephariglottis]. Notice the anther sac on the left has been removed by an unknown moth or butterfly and also the stigma is full of tiny grains of pollinia [pollen]. Pollination has been completed. Also notice the tiny hair's left behind by unknown insect [moth or butterfly]. Luzerne County, Pa. 7-26-23

Northern White fringed Orchid [Platanthera blephariglottis]. Notice the anther sac on the left has been removed by an unknown moth or butterfly and also the stigma is full of tiny grains of pollinia [pollen]. Pollination has been completed. Luzerne County, Pa. 7-26-23

Close up of the translucent anther sac, showing the pollinarium inside. Northern White fringed Orchid [Platanthera blephariglottis]. At the tip of the anther sac you can see the sticky viscidium.

Close up of the translucent anther sac, showing the pollinarium inside. Northern White fringed Orchid [Platanthera blephariglottis]. At the tip of the anther sac you can see the sticky viscidium.

Close up of the translucent anther sacs, showing the pollinarium inside. Northern White fringed Orchid [Platanthera blephariglottis].

Close up of the translucent anther sacs, showing the pollinarium inside [picture 1 above left]. Northern White fringed Orchid [Platanthera blephariglottis]. At the tips of the anther sacs you can see the sticky viscidium [picture 2 above right], when it [the viscidium] come in contact with Hummingbird Clear Wing Moth's eye, [Hemaris thysbe, a known pollinator] it will attach itself to the eye, and when the moth fly's away it will pull the pollinarium from the anther sac and takes the pollinarium to the next flower, and brushes the the stigma with pollinia [pollen]. Picture 3 [below] shows a Hummingbird Clearwing Moth with its left eye covered with as many as a dozen pollinarium.

The Wonders Of Orchid Pollination

Text And Photographs By David J. Hand

Figure 1

Figure 2

I have always wanted to try to better understand the pollination of orchids in more detail, and thanks to a spider my understanding of the mysteries of pollination have become a little clearer, at least for Platanthera species. I was watching a Hummingbird Clearwing Moth (Hemaris thysbe) moving from one P. blephariglottis to another when it suddenly stopped moving, and on closer inspection I found the moth had been caught by a well-camouflaged Goldenrod Crab Spider (Misumena vatia). The picture that I took enabled me to see the things that I normally wouldn’t have seen or noticed. Having travelled to many flowers, this moth was covered in pollinaria. With help from people more versed in the subject of orchid pollination then I will ever be, as well as doing my own research plus the picture that I took on that day, I now have a much better understanding of the wonderful and fascinating world of not just orchid pollination, but all flowers and their unique relationships and dependence on specific insects to achieve pollination and thus the continuation of its species.

[Figure 1]Shows the original picture, and [Figure 2] Is cropped to show how the flower of a White Fringed Orchid is pollinated. The moth is lured to the flower by a fragrant scent and the promise of a sweet reward. The flower in question has two anther sacs, which contain the pollen, these two anthers or anther sacs are separated by a gap in the middle and are parallel to one another. It is in this opening or gap between the two anthers that the moth places it's head the thus it’s proboscis into the spur. While probing deep within the spur for nectar, the moth’s eye is forced to come into contact with the viscidium, which is located at the tip of the anther, and it [the viscidia] are also sticky. As the moth leaves the flower, and as it does so, pulls the pollinarium out of one or both anther sacs.

[Figure 1]Shows the original picture, and [Figure 2] Is cropped to show how the flower of a White Fringed Orchid is pollinated. The moth is lured to the flower by a fragrant scent and the promise of a sweet reward. The flower in question has two anther sacs, which contain the pollen, these two anthers or anther sacs are separated by a gap in the middle and are parallel to one another. It is in this opening or gap between the two anthers that the moth places it's head the thus it’s proboscis into the spur. While probing deep within the spur for nectar, the moth’s eye is forced to come into contact with the viscidium, which is located at the tip of the anther, and it [the viscidia] are also sticky. As the moth leaves the flower, and as it does so, pulls the pollinarium out of one or both anther sacs.

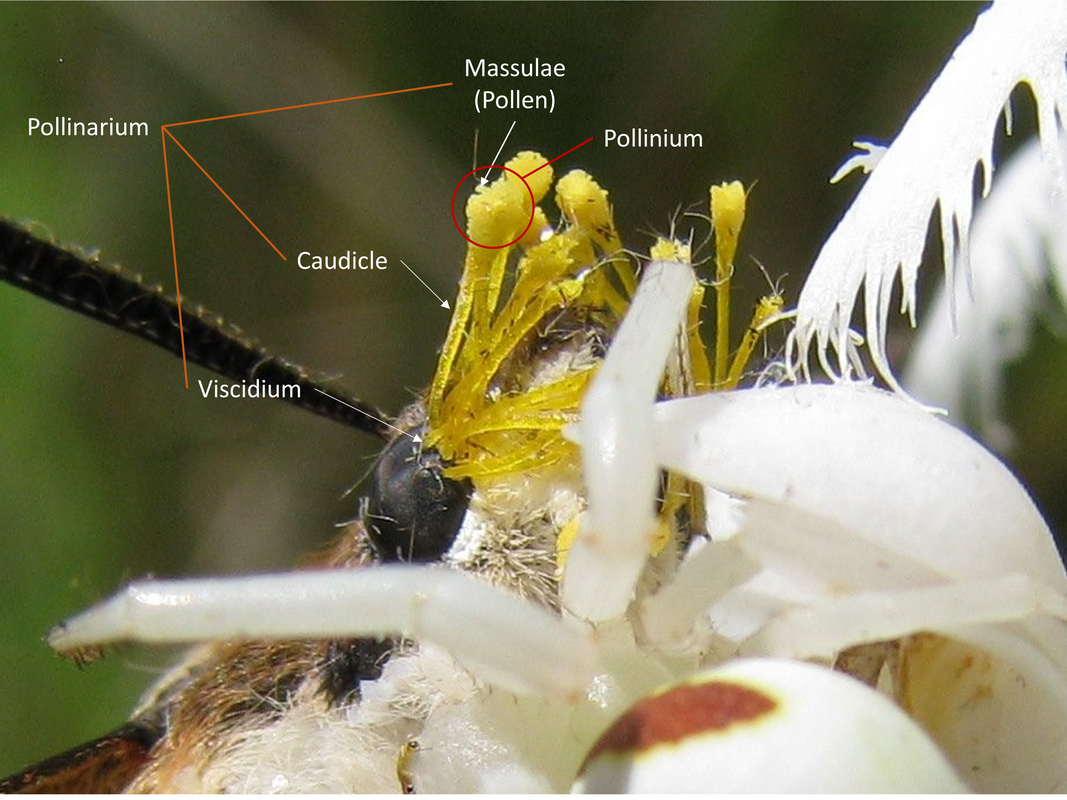

Figure 3

In [Figure 3] we get a closer look at just what it is the moth has removed from the anther sac[s]. Again, that which is stuck to its eye is called the pollinarium, the male part of the flower. You can clearly see the viscidium at the foot of each pollinarium, like little pads stuck to the moth’s eye. The yellow tube is known as a caudicle, and it connects the viscidium to the top, which is the pollinium, and forming each pollinium are many massulae, which are made up of tiny grains of pollinia that are bound together by viscid threads. The hope is, for the plant anyway, that when the moth visits the next flower and puts its proboscis in the spur that the pollinia, now attached to its eye, will brush against the stigma [Figure 4], the female part of that flower, and thus pollination will be achieved. What an ingenious trap the orchid has sprung on the moth to ensure that it gets pollinated, by directing the head of the moth and its eyes to line up with anther sacs, and leaves with the pollinarium which has the pollinia and then on to a stigma. For me this is just another example of the marvel of nature’s designs and engineering that I have spent countless hours photographing and trying to understand and now all because of a spider have a much clearer idea of just what I am looking at and feel privileged to witness.

It truly remarkable to think about how flowering plants form such specific and often complex relationships with insects to achieve pollination. Yet it is important to remember that these relationships do not form quickly, and instead are the result of trial and error over long periods of time. So, what we see before us today is nature at its best and is truly a work of art and perfection at its finest.

I would also like to state that I have on many occasions witness Spicebush Swallowtail Butterflies [Papilio troilus] on Planthera blephariglotis and it too has the long proboscis necessary for reaching down inside the spur of this flower and thus coming into contact with pollinarium inside the anther sac.

And this is only the pollination of Platanthera species discussed here, I can only imagine the other wonders waiting for me to discover in other orchid species and their amazing pollination.

It truly remarkable to think about how flowering plants form such specific and often complex relationships with insects to achieve pollination. Yet it is important to remember that these relationships do not form quickly, and instead are the result of trial and error over long periods of time. So, what we see before us today is nature at its best and is truly a work of art and perfection at its finest.

I would also like to state that I have on many occasions witness Spicebush Swallowtail Butterflies [Papilio troilus] on Planthera blephariglotis and it too has the long proboscis necessary for reaching down inside the spur of this flower and thus coming into contact with pollinarium inside the anther sac.

And this is only the pollination of Platanthera species discussed here, I can only imagine the other wonders waiting for me to discover in other orchid species and their amazing pollination.

Figure 4

I would like to thank Doran Horning for all his wonderful help with the graphics and his help in making my ideas more than just ideas. And also thank those who took the time to explain just what it is that I have been trying to capture all these years through my photography, the intricate and beautiful word of orchid pollination.

This article ordinally appeared in the "The Bulletin Of The American Orchid Society" In their December 2022 issue.

This article ordinally appeared in the "The Bulletin Of The American Orchid Society" In their December 2022 issue.